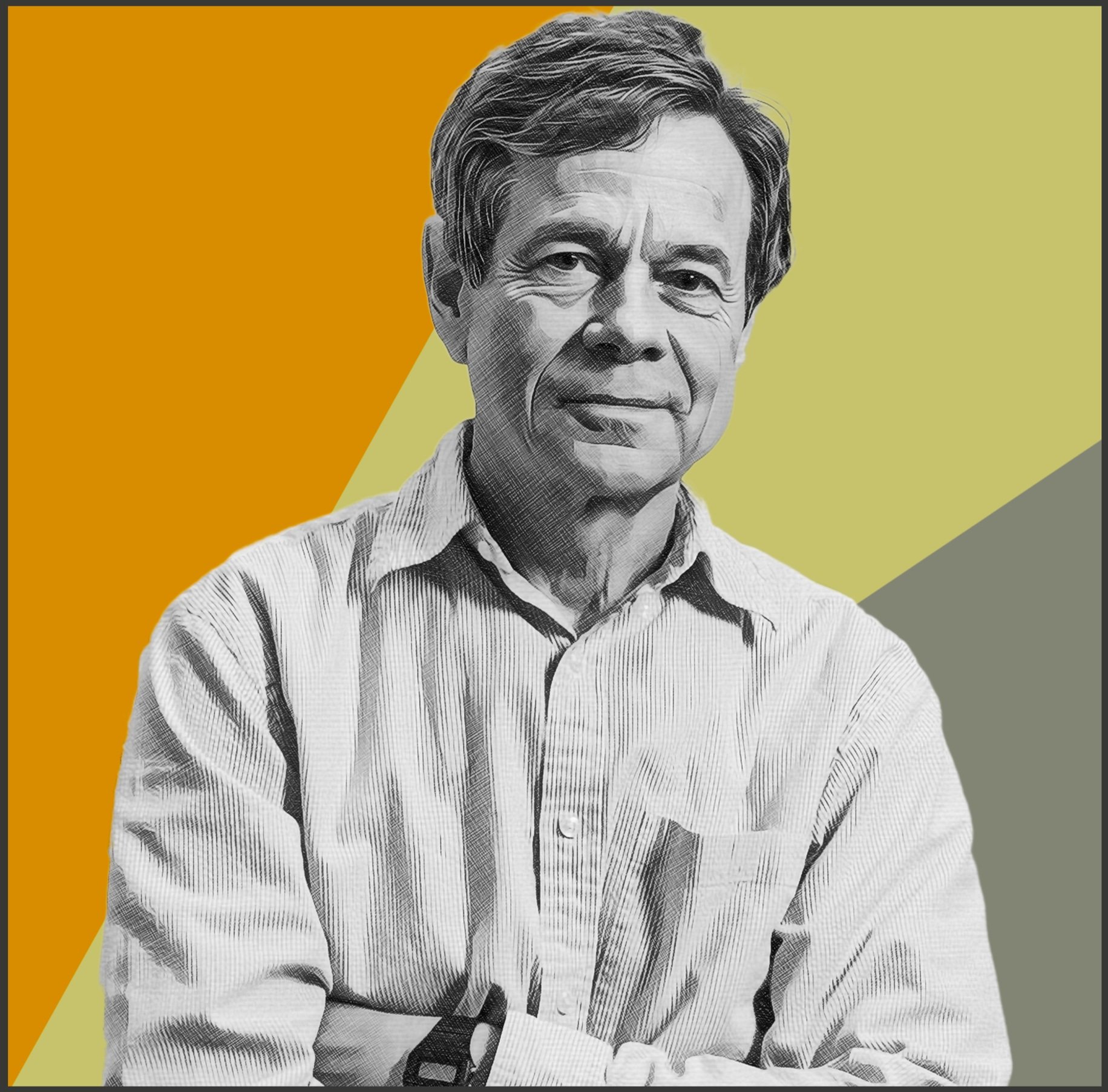

EP. 79: TRANSCENDENCE IN THE AGE OF SCIENCE

WITH ALAN LIGHTMAN, PHD

A celebrated theoretical physicist and humanist explores the role of faith and reason in modern science, the source of awe in life’s most transcendental moments, and the mysteries of human consciousness.

Listen Now

Episode Summary

When we gaze at the stars and wonder at our place amid the expanse of the universe, or when we witness the birth of a child and marvel at the miracle of existence itself, or when we listen to music that seems to touch our soul — there are moments in life when we feel a transcendent connection to things larger than ourselves. But how are we to make sense of these experiences in the age of science? In perhaps our most meditative episode yet, we speak with Alan Lightman, PhD, a theoretical physicist and humanist who holds a unique vantage point on topics fundamental to our existence: time, space, matter, and human consciousness. Dr. Lightman is Professor of the Practice of the Humanities at MIT, the author of numerous novels and books on science and philosophy, and the creator and subject of the 2023 PBS documentary series Searching: Our Quest for Meaning in the Age of Science. Over the course of our conversation, we discuss where our sense of awe comes from, the role of spirituality in a materialist world, whether or not human consciousness will ever be understood on a physical basis, the interplay of faith and reason in modern scientific practice, and more.

-

Alan Lightman is a physicist, novelist, and essayist. He was educated at Princeton University and at the California Institute of Technology, where he received a Ph.D. in theoretical physics. At MIT, Lightman was the first person to receive dual faculty appointments in science and in the humanities, and was John Burchard Professor of Humanities before becoming Professor of the Practice of the Humanities to allow more time for his writing. Lightman’s writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Granta, Harper's, Nautilus, the New Yorker, and the New York Review of Books, among other publications. His novel Einstein’s Dreams was an international bestseller and has been translated into thirty languages. His novel The Diagnosis was a finalist for the 2000 National Book Award in fiction. His most recent books are Screening Room: A Memoir of the South (2015), The Accidental Universe (2016), Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine (2018), In Praise of Wasting Time (2018), Three Flames (2019), Probable Impossibilities (2021), and The Transcendent Brain (2023). He is an elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and has six honorary degrees. Lightman is also the founder of the nonprofit Harpswell, which works to advance a new generation of women leaders in Southeast Asia.

-

In this episode, you will hear about:

• 3:58 - How Dr. Lightman found himself at the intersection of physics and creative writing

• 5:46 - The ways in which physics is the most “philosophical” science

• 9:13 - The definitions of ‘materialists’ and ‘vitalists’

• 11:56 - How Dr. Lightman conceptualizes his position as a ‘Spiritual Materialist’

• 16:07 - Contending with materialism despite awe-inspiring, transcendental experiences

• 22:30 - Whether or not Dr. Lightman considers himself a ‘reductionist’

• 25:28 - Where our sense of awe and appreciation of beauty come from

• 32:17 - The role of faith in scientific pursuits

• 34:20 - Finding meaning in a materialist world

-

Henry Bair: [00:00:01] Hi, I'm Henry Bair.

Tyler Johnson: [00:00:02] And I'm Tyler Johnson.

Henry Bair: [00:00:04] And you're listening to the Doctor's Art, a podcast that explores meaning in medicine. Throughout our medical training and career, we have pondered what makes medicine meaningful. Can a stronger understanding of this meaning create better doctors? How can we build healthcare institutions that nurture the doctor patient connection? What can we learn about the human condition from accompanying our patients in times of suffering?

Tyler Johnson: [00:00:27] In seeking answers to these questions, we meet with deep thinkers working across healthcare, from doctors and nurses to patients and health care executives, those who have collected a career's worth of hard earned wisdom probing the moral heart that beats at the core of medicine. We will hear stories that are by turns heartbreaking, amusing, inspiring, challenging and enlightening. We welcome anyone curious about why doctors do what they do. Join us as we think out loud about what illness and healing can teach us about some of life's biggest questions.

Henry Bair: [00:01:02] When we gaze at the stars and marvel at our small place amid the expanse of the universe, or when we witness the birth of a child and are struck by a sense of awe about the miracle of existence itself, or when we listen to music that seems to touch our soul; there are moments in life when we feel a transcendent connection to things larger than ourselves. But how are we to make sense of these experiences in our increasingly empirical and scientific world? In this, perhaps our most meditative episode yet, we speak with Dr. Alan Lightman, a theoretical physicist and humanist who holds a unique vantage point on topics fundamental to our existence: time, space, matter, and human consciousness. Dr. Lightman is professor of the Practice of the Humanities at MIT, the author of numerous novels and books on science and philosophy, and the creator and subject of the 2023 PBS documentary series Searching: Our Quest for Meaning in the Age of Science. Over the course of our conversation, we discuss where our sense of beauty and awe come from, the role of spirituality in a materialist world, whether or not human consciousness will ever be understood on a physical basis, the interplay of faith and reason in modern scientific practice, and more.

Tyler Johnson: [00:02:30] So this podcast is going to be a little bit different from some of our other episodes in a few respects. One is that Alan, as he has asked us to call him, is not directly involved with the health care profession in any obvious way. But at the same time, I feel like his, I don't know, philosophical or ethical or metaphysical bent is about as similar to that of mine and Henry's as anyone, perhaps, that we've spoken with. And so I'm particularly excited to talk to him because I think that he has a very direct and accessible way of approaching the very kinds of questions that matter the most to us and has done this in a very public way that I think has been enlightening and important. And I'm really excited to see what kind of fruit our conversation is going to produce. So thank you so much for being here with us.

Alan Lightman: [00:03:20] Thank you. Tyler, you said that I haven't had any direct connection with the health care profession, and that's mostly true. I have a brother who is an ophthalmologist, and I wrote a whole novel that took place largely within the health care system. It's called The Diagnosis. And there was a lot of medical material in that book. So sort of tangentially. Of course, all of us are connected to the health care system in some way or another because we all need medical help now and then.

Tyler Johnson: [00:03:51] Of course, and Henry will be joining your brother in the field in however many years when he finishes his training. So that'll be good. Well, maybe we can actually start out. Can you tell us what do you do? What's your job? Just explain it for for those of us who are not physicists, which I'm pretty sure is pretty much all of our listeners, maybe we have a few physicists out there for some random reason, but what exactly do you do?

Alan Lightman: [00:04:14] Well, I have several jobs. One of them is as an astrophysicist and physics, there's a pretty clear dividing line between experimentalists and theorists. And I am a theorist, which means that means that I work with mathematics and equations and computers. And I try to make predictions about astronomical phenomena like stars orbiting a black hole. And how would we be able to tell from their orbits that there's a black hole at the center? That kind of thing. But I also teach at MIT. For the last 25 years or 30 years. I've put most of my time into writing, so I'm probably more of a writer than a physicist now.

Henry Bair: [00:05:02] So can you tell us how the those two strands of your career, how did those come into play? Like, did one come first, then the other? Or has it always been, as far as you can remember, the two have been alive in you?

Alan Lightman: [00:05:16] Well, that's a great question. The two have been alive in me forever. When I was 8 or 9, ten years old, I had an interest in both science and the arts. I built rockets. I built remote control devices. I had a chemistry set. I was curious about how things worked, but I was also a reader and I wrote poetry and short stories. And so from a very young age, I was interested in both the sciences and the arts.

Tyler Johnson: [00:05:48] And how did you get to be a physicist specifically?

Alan Lightman: [00:05:53] Well, of all the sciences, physics attracts me the most because it's the most philosophical and I have a philosophical bent. I think at the frontiers of physics, we're very close to philosophy and theology. Those areas interest me a great deal. Physics is also the most fundamental of all the sciences. Of course we need chemistry and biology and the other sciences. They're vitally important. But if you're interested in understanding the universe at the most fundamental level, the level of of elementary particles and fundamental forces of nature, physics is your is your area.

Henry Bair: [00:06:36] One of the first things you mentioned was how philosophical physics is. And I'm not a physicist. I think I maybe took college level physics, basic physics just by way of my pre-medical requirements. Can you explain for for us what you mean by philosophical? Like what kinds of questions were you seeking to explore and what kinds of philosophical questions were you entertaining as you embarked on your more scientific explorations?

Alan Lightman: [00:07:07] Well, if you ask a question like "how did the universe come into being?" Or if you ask If you ask a question like "why is there something rather than nothing?" That question seems absolutely silly to most people, but a lot of leading physicists spend years worrying about that question "Why is there something rather than nothing?" So those are questions that I think for centuries lay in the domain of philosophy or theology. "How did the universe come into being?" There is another fundamental philosophical question, for example, which borders on both physics and biology, which is "do we have free will or all of our actions predetermined?" And if you're a strict materialist and you think that everything is made out of atoms and molecules and you believe in the cause and effect relationships, you know, Atom A pushes against atom B and atom B pushes against atom C and you get some result. Then you have a certain view of how the brain works, even though there's a lot about the brain that we don't understand. It looks like everything is predetermined. You know, if you have a sufficiently large computer and you knew the condition of every neuron in your brain and every synapse connecting them, and if you knew what all of the external input to the brain was, the visual and auditory, or you were in an isolation tank, so you didn't have any external input then in principle, a materialist would say that every future thought, every future action is already determined by the conditions of those neurons. Those are two philosophical questions. How did the universe come into being? Maybe why did it come into being? And free will versus determinism, which are old philosophical chestnuts, but also now have been brought into the realm of science.

Tyler Johnson: [00:09:13] So in a minute here, I want us to launch together into what I hope will be a larger sort of a continuous conversation session about some of these really important philosophical questions where I hope there will be a through thread that carries us through much of the rest of our time together. But before we get to that, I think it's important that we define a few important terms, some things that come up in these discussions, but that most people may not have heard much about or maybe don't know what they are. So can you first tell us what is a materialist and what can a materialist believe in and not believe in?

Alan Lightman: [00:09:49] Well, I mean, the word materialist is used commonly in the vernacular to mean someone who likes nice clothes and fast cars and big houses.

Tyler Johnson: [00:10:00] Just like you. Right, Alan?

Alan Lightman: [00:10:01] Just like me.

Tyler Johnson: [00:10:03] That's your big thing.

Alan Lightman: [00:10:05] But by materialism, I mean it literally that everything in the universe is made out of atoms and molecules and nothing more. Maybe the energy that is exchanged between atoms and molecules. But. But that's all there is. There are no there's no non-material essence that is part of the world. An example of a non-material essence would be the soul or the mind as being separate from the brain. So that's how I define materialism for me.

Tyler Johnson: [00:10:39] And what about a vitalist?

Alan Lightman: [00:10:41] A vitalist is a person who believes that that in living organisms, that there is some non-material energy or force that is present, that does not follow the laws of chemistry, biology and physics. And it's a non-scientific thing. In other words, for centuries, as you know from asking the question, there was a debate about whether living things had some special essence that was different from non-living things. In recent years, certainly in the last century, that all modern biologists are materialists or they call themselves mechanists. They are anti-vitalists. They don't believe that there's any non-material essence that living matter follows the same laws of chemistry, biology and physics that non-living matter does. Of course, living matter has a certain special arrangement of those atoms and molecules that lead to properties that we associate with life, like the ability to to utilize energy, the ability to grow and evolve, the ability to reproduce.

Henry Bair: [00:11:56] So, you know, you mentioned earlier to us what materialism means to you. Yet at the same time, on many occasions in your writings and your speeches, you've described yourself as a spiritual materialist. Now, given that within the precepts of materialism, there isn't you know, you mentioned words like soul or the mind or the spirit, even as being just not within a part of that framework. How do you conceptualize spiritual materialism? What does that mean to you?

Alan Lightman: [00:12:25] Well, different people have different meanings of spirituality. My meaning, my understanding, which is a non-theist definition, is a bunch of of experiences. Feeling that you're part of something much larger than yourself, feeling a connection to nature and to other people, the appreciation of beauty, the experience of awe. These are all experiences that I grouped together under the heading of spirituality, and they may or may not involve God. For me, they don't involve God. So I have a that's why I say I have a non-theist understanding of spirituality and I believe that there is no conflict or contradiction at all between materialism and spirituality, as I have just defined it.

Tyler Johnson: [00:13:20] So Alan, you have written a lot over the years, right? Many books and essays and novels, as you mentioned. You've had many you've given many speeches and and all the rest. So there was a PBS, a three part PBS special that in effect, I think, tried to sort of distill down some of the essence of what you have thought and written about over the years into a sort of a narrative arc that would allow you to weave some of the biggest questions that you have asked and tried to seek answers to into this one PBS special to the degree that that's possible. But the one thing that I really like from that is that I thought that its framing of- there's a number of specific questions, but there's the one big question and I think the way that it frames that big question is really nice. And so I was hoping that though I know you've done this in many other forums before, can you tell us about the night under the stars in Maine? That is kind of the launching point for that. And then I have some questions that I want to ask in follow up to that. But but tell us about that experience.

Alan Lightman: [00:14:29] Okay. Well, thank you. For many years, my wife and I have spent our summers on a small island in Maine. My wife is a painter and she paints and I write during the summer. And we feel very privileged to have that opportunity. And it's a very small island. There are only six families who live on the island and each family has their own boat. There are no bridges or ferry service to the island. So one night I was coming back to the island very late after midnight, in my boat, I was alone. There were no other boats on the water. It was a very clear night and I could see the stars very clearly in the sky. And I decided to turn off the engine of the boat. And then I decided to turn off the running lights of the boat. And it got even darker and clearer. And I lay down in the bottom of the boat and just looked up. And after a few moments, I felt like I was falling into infinity. I felt like I was merging with the stars, that I was merging with something much larger than myself. I think all of us have have have had experiences like that, maybe not that exact experience, but we've had experiences where we feel connected to something much larger than ourself. I don't know how long I lay there looking up because I lost track of time. That was a part of the experience. But after a while I sat up and started the engine again and went home. So. What was that?

Tyler Johnson: [00:16:07] And we'll get to some of the implications more in a second here. Before we do that, though, I want to do two things. So the first is and I don't know how well the technical aspect of this is going to work, I'm just going to kind of hope So. We have talked a lot on the program about what have become some of our favorite words, which are words like mystery or transcendence or the ineffable or whatever word you like to use, which I think your experience under the stars in Maine is a sort of a pinpoint one moment in time, right? An example of some of those words, however you would choose to describe it, but to try to put our listeners into a similar frame of mind, I'm going to pay about 90 seconds of a choral song just for us to listen to and to get us into a similar state of mind. So we'll see if this works.

VOCES8: [00:16:58] O Magnum Mysterium, by Morten Lauridsen, performed by VOCES8

Tyler Johnson: [00:17:59] So that's about 60s of O Magnum Mysterium is sung by VOCES8, written by by Morten Lauridsen. And then I want to read this quote. So this quote is from an essay written by Bertrand Russell right towards the beginning of the 20th century. So Bertrand Russell was a very famous philosopher who was one of the earlier and most forceful and eloquent proponents of materialism, among other things. So he wrote a very famous essay called A Free Man's Worship. And part of in part of that essay, he says, quote,

Tyler Johnson: [00:18:32] "That Man is the product of causes which had no provision of the end they were achieving; that his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and his beliefs, are but the outcome of accidental co-locations of atoms; that no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling can preserve an individual life beyond the grave; that all the labors of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and that the whole temple of man's achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the debris of a universe in ruins -- all these things, if not quite beyond dispute, are yet so nearly certain that no philosophy which rejects them can hope to stand. Only within the scaffolding of these truths, only on the firm foundation of unyielding despair, can the soul's habitation henceforth be safely built."

Tyler Johnson: [00:19:38] So in my estimation, and obviously I'm not trying to put words in your mouth, so correct me where I'm wrong, but in many ways I see your lifetime's project as grappling with the tension between the experience that at least I have when I listen to O Magnum Mysterium or that you had under the stars that night in a rowboat in Maine, and the powerful, eloquent, forceful rhetoric of Bertrand Russell. Right. The idea that everything can be reduced to molecules and atoms, as you said, and that there is no meaning beyond that and trying to figure out...how can that be, right? How can that that starry sky experience in Maine happen if all we are is atoms and molecules?

Alan Lightman: [00:20:34] Well, I don't agree that there's no meaning in the atoms and molecules.

Tyler Johnson: [00:20:41] Elucidate that for us; it seems to be a tension, right?

Alan Lightman: [00:20:45] Oh, it's definitely a tension. And of course, it's a great puzzle. And a challenge to understand how these complex human experiences we have can arise from mere atoms and molecules. But when you start talking about meaning, that's a totally different issue. Now, first of all, I think that I don't believe that there's any absolute meaning in the cosmos. I think that each person has to find meaning for themselves, their own meaning. So for me, and I can only speak for myself, my life has meaning even though I'm made only of atoms and molecules. And at some point in the future, maybe in my case, another 25 years, those atoms and molecules are going to disassemble and they're going to scatter in the wind and the ocean and the air and the...and the ground. I still think that I'm part of of a long chain of humanity, extending back hundreds of thousands of years, maybe millions of years, and will continue into the future, even when we're part machine and part human, that I'm part of that long chain of being. And not only that, I mean, looking in the past, the far distant past and the far distant future, that right now, during my very limited brief lifetime, I have meaning in affecting other people trying to make the world a slightly better place. So that's meaning for me.

Tyler Johnson: [00:22:30] And I'm curious. So another term that we didn't define earlier, but that's related to ones that we were talking about is to be a reductionist. Right? The idea that so for instance, in the PBS program, you spend a long time talking with both philosophers and neuroscientists about whether if you could adequately capture the firing and conditions and whatever of every neuron, could you perfectly predict what every human is going to do in every instance? Right. And if the answer to that question is yes, then that's a perfectly reductionistic explanation for our behavior. Do you consider yourself to be an absolute reductionist and if so, why? Or And if not, why not?

Alan Lightman: [00:23:14] Well, I think I'm a reductionist in the sense that I do believe that we're made out of atoms and molecules and nothing more, and that that our atoms and molecules obey the laws of physics. And I believe in cause and effect relationships. So I'm a reductionist in that sense. But in terms of our mental experience of the world which takes place in the brain, we know that the unconscious brain calls 90% of the shots. There's a vast amount of activity and even decision making in the unconscious brain. And by definition, we're not conscious of all of that. And sometimes when we suddenly feel like we've made a spontaneous decision about something, that actually that decision has been made by our unconscious brain working diligently. And there even been some laboratory experiments by famous biologists named Libet that demonstrated this, that decisions are actually made a split second before or maybe several seconds before we're consciously aware of having made the decision. So even though I'm a reductionist, I do think that in terms of the conscious mind -the conscious brain (and of course the mind and the brain are the same thing for a biologist or a scientist) our conscious self is still subject to mystery, to unforeseen events, thoughts that appear to be random. And so our brain is a little bit like a black box and we're sitting on the outside of the box. The black box is the unconscious brain. So as far as our conscious brain is concerned and our our conscious experience of the world, the fact that everything is reductionist inside the black box does not make everything reductionist outside of the box.

Henry Bair: [00:25:28] So then here's my next question and maybe it's just an intellectual exercise. We've been talking a lot about experiences of transcendence and awe; from your moment under the starry sky to that clip of music Tyler played to our sense of connection to nature. There's so much of what's going on in these moments that we just don't understand. As you said, it's a black box, whatever is happening in our minds. So then awe and beauty, these emotions, if you can even call them that, do they only hold power because we don't know what explains them? If at some point we did get to an understanding of this black box of how the human consciousness works and the mind processes these sensations, would that change how you felt about it? Does it reduce the awe from contemplating what the soul is able to experience?

Alan Lightman: [00:26:24] It's a good question, and I think it would have some effect, but I don't think it would eliminate the emotional experience. I can give you an example. I, as a physicist, I understand exactly how rainbows work. The sunlight is a mixture of many wavelengths of electromagnetic energy. Each wavelength corresponds to a different color. And when those colors are all mixed together in sunlight, when that light strikes, the water molecules in the sky, different wavelengths have different trajectories through each water molecule. And that causes the colors to fan out. And I understand why the the arc of the rainbow is about 43 degrees, that that also comes about by basic physics. And so I understand quite a lot about how rainbows work. I mean, even in a more detailed level than I just described, I understand why different wavelengths have different trajectories. It has to do with the way that the electrons and atoms vibrate with different wavelengths of electromagnetic energy that hit them. So I know all of that. But when I look at a rainbow, it still takes my breath away. I'm still awed by the the sight and the experience. So getting back to your question, I think that even if we did know everything inside the black box, even if we did understand how consciousness arises from atoms and molecules, and that would include unconsciousness as well, I think that our emotional life would still exist. And I think we would still fall in love and still admire rainbows and spiderwebs and all the other amazing phenomena that we see.

Tyler Johnson: [00:28:21] I guess that's another way of getting toward the question that I was trying to pose earlier when I asked if you were an absolute reductionist, and then you responded in part by talking about what's inside the black box and outside the black box, and you believe that part of it can be reduced and part of it can't. But but but to your point. Right. I mean, I'm not a physicist, right? So I don't have anywhere near the depth of understanding of the manipulation of the physical parts of the universe that are happening with a rainbow or a plainchant or anything else. Right. And you could go on about any of those things much longer and and with more coherence than I could. But I have enough of an idea, right? Like, I know that when I listen to music that there are sound waves propagating through the air and, you know, et cetera. Et cetera. And harmonious, you know, combinations of notes and what have you. But partly to the point you were making a moment ago, what so strikes me is that the whole seems to be so much more than the sum of the parts. Right. There seems to be. And and you go into this in great detail in the PBS special talking about the idea of consciousness. Right. That even though we can even know, we know so much more through fMRI and all these other things about neurobiology than we used to, there just seems to be a remainder. Certainly there's a remainder that's outside of current scientific understanding, but it makes you wonder. You almost seem to be skeptical of your own materialism or skeptical of your own reductionism, in a sense, at least as a full explanation of the entire experience of love and pain and suffering and everything else that it means to be human. Is that fair or does that go too far?

Alan Lightman: [00:29:54] Well, I think that that's fair. If we look at consciousness as sort of the fundamental mental experience on which everything else is based. Even when we understand all of the interactions of neurons and we understand already extremely well what happens in an individual neuron, we know how the calcium and potassium gates open and close to let ions in. We know how electricity flows down the neurons. We know the chemicals that neurons exchange with other neurons at the synapses.

Tyler Johnson: [00:30:33] Henry and I are having nightmares of medical school exams as you're talking. So you better stop or we're going to pass out or something.

Alan Lightman: [00:30:40] I figured I was pushing some buttons with that, even though we know all of that. We still don't know and may never know how this feeling that we have, this sensation caused by all the electrical and chemical exchanges between neurons, somehow that sensation produces this feeling of having a self. Of having an ego or having an I, of of being in the world, of being able to plan for the future. And that's a feeling that arises from all of these electrical and chemical exchanges. It may be that we've gotten, you know, that we can't really completely say how that feeling arises that we can't quantify it. There's a neuroscientist named Robert DeSimone that I actually talked to in the PBS series, and I'll talk to him about consciousness. And he says that asking what consciousness is, is like asking where in a car is the speed located? Mm. He says, Well, consciousness is an overrated thing concept. He says eventually we'll know how all of the neurons work and how they exchange information with each other, and that'll be that. And anything further that we ask about our understanding, like what is consciousness is just the wrong question to ask.

Tyler Johnson: [00:32:17] Yeah. You know, I was struck in the PBS series, there was another time when after you spoke with the doctor you were just referring to, you spoke with a philosopher about the sort of philosophical implications on consciousness and free will and all the rest. And she said something to the effect that we are still waiting for the Copernicus of consciousness, right. That we're still waiting for the person who's just going to blow up our understanding and give us a completely different frame of reference. One of the many things that's so interesting to me about those quotes is the fact that it is interesting to me that scientists are required to some degree to place what I can't think of a better word than faith in the future of the ability of science to answer some of these most fundamental questions. Right. And I mentioned that mostly because one of the things that we've talked about before on the podcast is that in the 20th century in particular, there's grown to be this great schism as it's often popularly perceived between science and religion or spirituality or whatever you want to call it, which seems to suggest that religion rests on faith and science rests on facts. But it seems to me that both of them need both things, right? Both of them are trying, as you said, and at some point they converge where you have physics trying to answer both. I mean, we don't usually think of them as theological questions, but in a sense they are sort of theological questions and both need both facts and faith, it seems to me. Does that seem fair?

Alan Lightman: [00:33:45] Yes, that seems fair. I agree with your point that that science operates on faith also, and the faith that science has as the principal article of faith is that the universe is lawful. And lawful everywhere in the universe. It obeys laws that human beings are capable of discovering, even if it takes us, you know, another thousand years or longer. That said, I think religion and science are very different in how they go about acquiring knowledge.

Tyler Johnson: [00:34:20] Well, since our time is so limited, let me instead bring it back around to something that I think is particularly important for our audience. As you may have gathered, and I think we mentioned briefly, a large part of the impetus for this podcast is that there's an epidemic of burnout amongst physicians, right? So if you look at there's all kinds of survey data that up to a quarter of physicians are seriously thinking about leaving the profession because they feel so alienated from their jobs. And there's a great deal of survey data that shows that physicians just no longer find meaning in their work. And part of the reason that we think that your work is so important to the discussions that we have on this podcast generally is because as a scientist and a materialist and a reductionist, even if not quite absolute and whatever else, you have still managed to rest deep, even don't know if you'd use the word, but seemingly transcendent meaning from all of the kinds of experiences that we've talked about. And so I guess I'm wondering what advice can you give to a community of people who are dedicated to science and evidence and scientific discovery about how to still find that kind of transcendent meaning in a world that often seems to have lost its sense of meaning over the last 100 or so years.

Alan Lightman: [00:35:49] Well, first of all, I have a brother who's an ophthalmologist and I gave a lecture once in a community. This is Winfield, Pennsylvania. A lot of people came up to me after the lecture who had been patients of my brother and said "He helped me to see." And I can't think of any more direct or powerful or immediate way that you can have an impact on the world than helping people to see or curing an illness. So I'm speaking now not as a physician myself, but I think there's tremendous meaning in being able to help other people in that way. I mean, all of us want to make a difference in the world except for the extreme egocentrics. We all want to to make a difference. We all want to make the world a better place. And in medicine, I think you do that in a very direct way. And I admire that tremendously. The other thing I would say is I would refer to a Hindu word called darshan. Which means literally being open to the divine. But I interpret it more generally to be open to the world, to be open to experience, to be open to adventure, to be present in the world. To be mindful, to use a Buddhist term. And I think that if you can be open to the world in that way, that it greatly enriches your life. And finds meaning even in small things like having a good meal with friends, but especially in the field of medicine where you are literally helping people to see. Or two to recover from an illness or to endure an illness. The palliative care. That you are really participating in the world in a very direct and powerful way.

Henry Bair: [00:38:13] Thank you. Um, yeah, I mean, as a, hopefully a future ophthalmologist, that that means a lot to me. I have one question that I would love to ask. It is a bit personal, so feel free to let me know if it's if it's a little bit too personal. But, you know, I can't help but notice that throughout your writings you reference Jewish teachings, Christian teachings. You go on walks with Buddhist monks and you cite Hindu scripture. So it's clear you thought deeply and explored various faith traditions from around the world. And after all of those explorations, I would love to ask, you know, are you still looking for religion? What what is your where is your heart? You know, when it comes to finding a religious tradition?

Alan Lightman: [00:38:55] Well, I'm I'm still looking for meaning. And I as I said earlier, I think for me, meaning part of meaning is making the world a better place, which is an ongoing lifetime pursuit. I'm looking for new experiences. I am making new friends. One of the precepts of all religions, which which I really hold close to my heart, is the Golden Rule. To do unto others as you would have them do unto you. Who was the great medical person who said do no harm? Is that part of the Hippocratic Oath? I'm not sure.

Tyler Johnson: [00:39:39] Yes, that's the sort of the opening salvo.

Alan Lightman: [00:39:42] Yeah. So one version of do no harm is do unto others as you would have them do unto you. And I think that's a great moral precept to live by. And it seems to be fundamental to all of the religions in the world. So I think science and religion have both done a lot of harm. And they've also both done a lot of good.

Tyler Johnson: [00:40:11] Can I ask along the same lines and again, you know, anything that's too personal, you can just say so. But just to be open, I consider myself a pretty hardheaded empiricist right When I'm sitting down in the cancer clinic with patients, I don't give them prescriptions of chemo based on my feelings. Right? I pull out kaplan-meier curves and survival statistics, but I also consider myself a theist and part of the reason for that- so in the PBS special, one thing you referenced the the philosopher that you were I can't remember her name, but that you were speaking about.

Alan Lightman: [00:40:43] Rebecca Goldstein.

Tyler Johnson: [00:40:44] Yeah, exactly. Consciousness and whatnot with you say "we agree that the material universe shows no evidence for caring for us." And, you know, I will admit that part of I guess for me and, you know, I recognize that this could be considered an appeal to ignorance in some quarters. But the fact that I can't quite convince myself to be an absolute materialist that I listen to O Magnum Mysterium and more than the sound waves is the beauty. It's that gap, the presence of the beauty and the thing the beauty does to me. I guess if I had to list an evidence for why I am open to the idea of a theistic presence behind all of the atoms and molecules in which I also believe it would be that inexplicable gap. Does that hold any resonance for you? I'm genuinely curious.

Alan Lightman: [00:41:39] I totally respect that point of view.

Tyler Johnson: [00:41:41] Yeah.

Alan Lightman: [00:41:42] And of course, I think far more than 50% of the world population believe in an all powerful, intelligent being, that created the universe purposefully. That includes many very, very smart, wonderful people. For me. I don't think it's necessary to believe in an all powerful being, to be fully appreciative of the kind of ephemeral, numinous experiences that you're talking about and listening to that music and that I felt when I was looking up at the stars.

Tyler Johnson: [00:42:17] And I agree with that. I just want to be clear that I don't I'm not questioning the validity of coming to the opposite conclusion.

Alan Lightman: [00:42:24] Yeah, I think that the world is is amazing and wonderful, even if it's just made out of atoms and molecules that those atoms and molecules are capable of some pretty extraordinary things. There's a concept in science in the last few decades called emergent phenomena. In which a complex system of many parts can have a qualitative behavior that cannot be understood on the basis of the individual parts. And of course, the human brain is the paragon example of that. So I. I don't feel there's any conflict between my being a materialist and a spiritual person and sort of I'm going in circles now, back on that territory.

Tyler Johnson: [00:43:16] You live in that tension you inhabit the tension.

Alan Lightman: [00:43:18] I inhabit that tension. And I find that that tension is for me, is very a source of my creativity. And I like to think that I'm open to these numinous experiences. I feel that that even atoms and molecules are capable of extraordinary things.

Tyler Johnson: [00:43:38] I want to ask one more question, and as someone who's living such an intentional life and who has thought so much about life in general, about him, what your life is also about: when you die and the people who love you most come, if you have a funeral to speak at your funeral, what do you hope they'll say?

Alan Lightman: [00:44:00] That they loved me. That's enough.

Henry Bair: [00:44:05] Powerful. Well, with that, we want to thank you so much for taking the time to join us, for sharing your story, for opening up about all of the thoughts, the wonderful thoughts you've had over the years. It's been a true pleasure and privilege to speak with you. I, for one, have truly enjoyed your meditative writings, and thank you so much for putting your thoughts out there.

Alan Lightman: [00:44:25] Well, thank you, Henry, And thank you, Tyler.

Tyler Johnson: [00:44:27] I will also say that I just I feel like there are very few public intellectuals who are willing to really go to the mat to wrestle difficult issues. Like, I feel like most people kind of operate within their niche, and then when they get to one of the difficult issues, it's like, well, maybe ask the rabbi or, you know, something like, that's somebody else's department. And so I really deeply appreciate your willingness to grapple with the things that I think really matter the most. I think it's really, really important to see people who are brilliant scientists and empiricists and whatever else who are willing to ask those bigger questions. I think it makes society a better place. So I'm really, really grateful.

Alan Lightman: [00:45:10] Thank you, Tyler.

Henry Bair: [00:45:13] Thank you for joining our conversation on this week's episode of The Doctor's Art. You can find program notes and transcripts of all episodes at www.thedoctorsart.com. If you enjoyed the episode, please subscribe rate and review our show available for free on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts.

Tyler Johnson: [00:45:32] We also encourage you to share the podcast with any friends or colleagues who you think might enjoy the program. And if you know of a doctor, patient or anyone working in health care who would love to explore meaning in medicine with us on the show, feel free to leave a suggestion in the comments.

Henry Bair: [00:45:46] I'm Henry Bair.

Tyler Johnson: [00:45:47] And I'm Tyler Johnson. We hope you can join us next time. Until then, be well.